Alternative Processes: A Contemporary Practice

23rd May 2023

When viewing photography, a common question asked by collectors or enthusiasts is, “is this an original?” A tricky question to answer, when an original, in its truest sense, would likely be the negative. While photographs can certainly be rare and valuable—such as a vintage print or one of the only known prints in existence—photography is a medium praised for its reproducibility. Therefore, it is relatively uncommon to find a photograph that is truly ‘unique’.

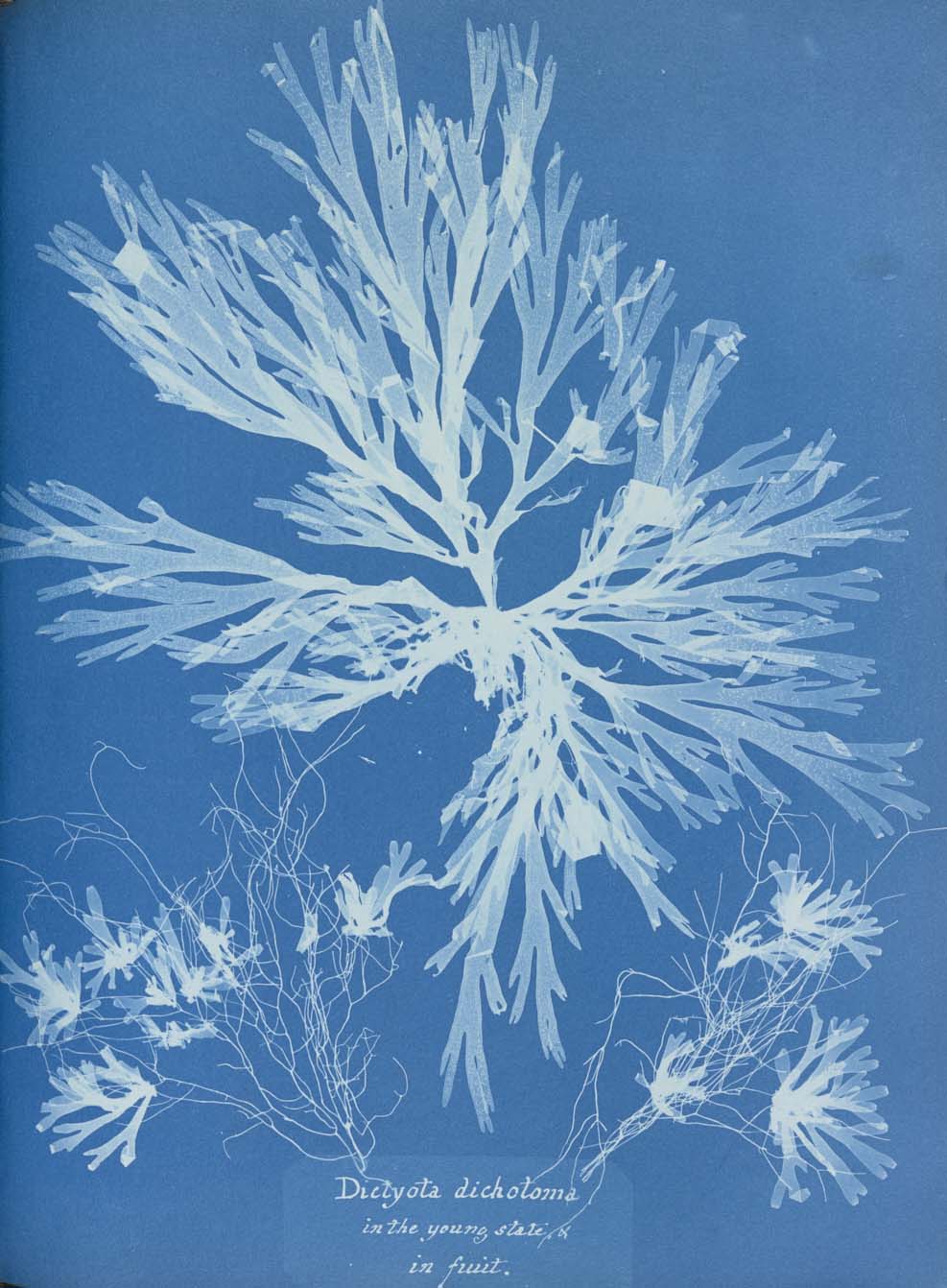

The first photographic negatives made were, in effect, photograms. The phenomenon of the shadow has peaked human curiosity since the stone age, but in the 17th century, scientists and artists alike experimented with capturing the fall of light and shade on a surface with the aim of preserving its image. William Henry Fox Talbot called photograms ‘photogenic drawings’, which he created by placing leaves onto sensitised paper and exposing them in the sun. The result was the object’s white silhouette against a dark background—an inverted shadow. Many pivotal artistic experiments were to follow, such as Anna Atkins’s seminal ‘British Algae’ from 1843, which utilised the similar cyanotype process. Fast-forwarding into the early 20th Century, many modern art movements also engaged with the photogram, such as Dadaism, Constructivism and Surrealism. It also became an aesthetic strongly associated with the Bauhaus, in formalist dissections of architecture. Photographer’s like Man Ray were especially drawn to the photogram for its ability to abstract and distort; to interpenetrate form. So much so, that he attempted to personify the process by coining the term ‘Rayogram’.

Photograms and cyanotypes are classified as ‘alternative’ photographic processes; a term that generally refers to historical or non-traditional methods of creating photographs. Tintypes, gum bichromate prints, chemigrams and lumen prints are also examples. Many of these processes involve an element of unpredictability, using materials that are difficult to control or involve a deliberate incorporation of randomness. The results are often aesthetically distinct prints that are unique and not reproducible. As a technically complex craft, collectors appreciate the dedicated-labour involved, the rarity, the experimental and creative nature of the prints, and the connection to photography’s early roots. As a result, works made from these traditional processes can command significant prices on the market.

In recent years, some contemporary photographers have shown a renewed interest in these hands-on processes, perhaps as a response to the detached air of digital printing. While some artists are drawn to the history of a specific technique, others enjoy the way that certain chemicals can be handled almost like paint. This re-engagement demonstrates an enduring urge to test the remits of photography, pushing at its ever-expanding technological limits and exploring its artistic capabilities.