Equilibrium and Geometry: Henri Cartier-Bresson in Madrid

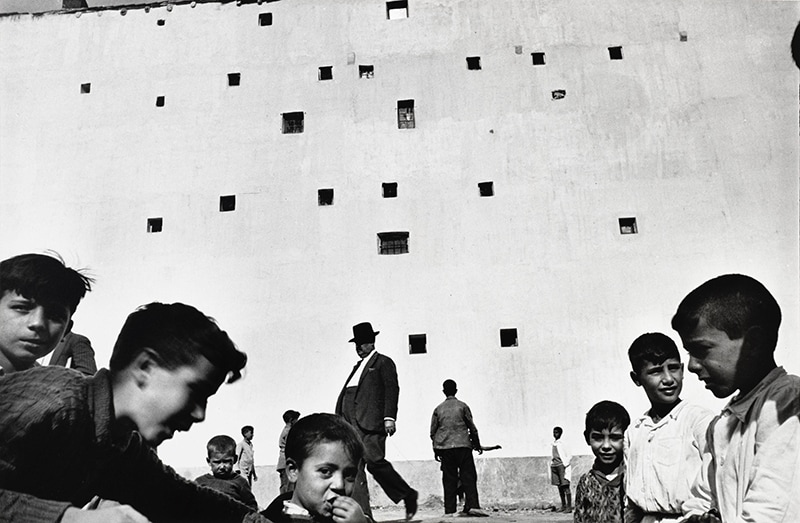

Henri Cartier-Bresson lived and worked by his mantra of ‘the decisive moment’ which he defined as “the simultaneous recognition in a fraction of a second of the significance of an event as well as of the precise organisation of forms”. For Cartier-Bresson, the photograph had to contain significant content that was arranged into rigorous composition. ‘Madrid, Spain, 1933’ is exemplary of his unrivalled ability to harness ‘the decisive moment’ to make photographs of extraordinary visual resonance.

Cartier-Bresson started using a 35mm Leica camera in 1932. He would refer to his camera as the “extension of my eye” and travelled across Europe with his friends, artist Leonor Fini, and writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues. The small Leica allowed him to capture the movements and transformations on the streets of European cities as he travelled.The complex geometry of this photograph, taken on the streets of Madrid, rests on the relationship between the high wall in the background, with its strange, small windows, and the children in the foreground. As the viewer’s eye is drawn through the image, the tightly angular shapes of the windows morph into the fluid movement of the playing children. A boy glances towards the photographer, making the viewer aware of the strange, low positioning of the camera.

The rise of Modernist photography in the 1920s had championed pattern, form and line in photography over figuration. Cartier-Bresson was always searching for equilibrium and geometry. He remarked that, “if the shutter was released at the decisive moment you have instinctively fixed a geometric pattern without which the photograph would have been formless and lifeless”. Having trained in the academy of the Cubist painter, André Lhote, Cartier-Bresson was well-versed in the principles of Cubism and intended geometry to create structure from which order could be derived amidst the chaos of life. In this photograph the geometry of the windows is contrasted by the curve of the figure of the man who walks through the scene. Creating a rhythmic flow between the background and foreground, the man’s hat mutates into another black space like the small windows. As the man glides past the geometric backdrop and the boy in the foreground simultaneously confronts the photographer, the scene becomes cinematic, rife with Surrealist encounters. Cartier-Bresson socialised with the Surrealists at the Café Cyrano in Paris and learnt from their urge to access the subconscious by seeking the uncanny within the everyday. Taking Surrealism out of the studio and the Paris salons, Cartier-Bresson found the surreal on the streets of Europe.

1933 saw Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany and the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States with promises to steady the wavering nation whilst in the grips of the Depression. Spain was in the midst of huge political unrest and violence spread through the country as the Socialist opposition fought against the Fascist government. Yet Cartier- Bresson’s masterpiece from his travels through the Iberian peninsula looks to form and shape rather than politics. The photograph is full of movement and energy, typical of his early work. The photograph is evidence of the problematic task of trying to define Cartier-Bresson’s genre. Often transcending historical and political context, his photography is not simply documentary as formalism, abstraction and lyricism all enter into his frame of reference. As Peter Galassi has said: “In the thirties, Cartier-Bresson had discovered that photography possessed the power to reinvent experience so radically that it could transform child’s play into cosmic rapture”.